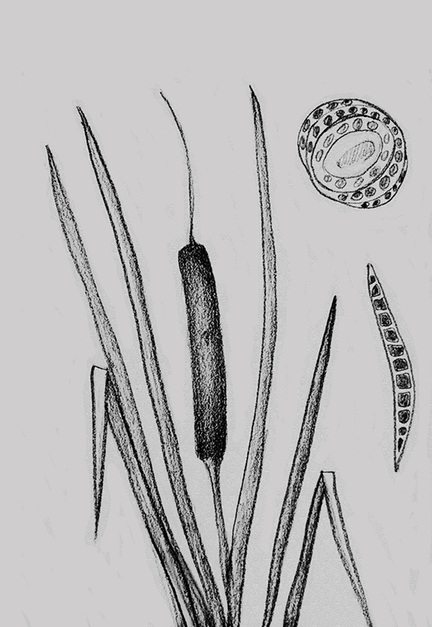

There are various species (about 30) within the genus Typha, spread through wetlands all over the world. Our local cattail is usually Typha latifolia. Each plant has both male and female flowers, which is not unusual in the plant world. The male flowers are at the top, where they wither after the pollen has dispersed. The female flowers are clustered further down the stalk, where they form the “corn dog”. The seeds are individaully attached to tiny fibers. In late summer and early fall, the seeds will loosen and float away on the fine fibers.

Cattails increase their numbers by seed and by growth of the rhizomes. They prefer muddy, marshy areas such as creek banks and swamps, and do well with the fluctuating water levels of wetland areas. Cattails spread very quickly, crowding out many other plant species. They can grow up to 10 feet tall, but ours are usually 4 to 7 feet tall.

How does the cattail plant support such long, slender leaves that stick straight up from swamp muck? The answer lies in a structure called an aerenchyma (pronounced like “a-RENG-kim-ma”) – these are air spaces spread throughout the stems and leaves of the cattail plant. You can see sketches of them in cross section on the right side of my drawing. The open spaces surrounded by tough cellular walls make for a lightweight but sturdy structure that can hold up the slender cattail leaf from bottom to top. In a general way, you could compare it to the structure of corrugated cardboard.

Cattails have several functions in their native ecosystems. The seeds, leaves, and rhizomes are edible. Many animals nest or shelter among the plants – waterfowl, redwing blackbirds, deer, raccoons, muskrats, frogs, turtles, and tiny animals called macroinvertebrates. Birds use cattail fluff to line their nests.

Various groups of people around the world have found a use for almost every part of the cattail plant – they have eaten starch produced from the rhizomes, the young leaves, the pollen, even the unripe “corn dog”. The leaves have been used to weave baskets. The leaves can be broken down into long fibers, which can be used to twist ropes or to make fabrics. The seed fluff can be used as tinder to start fires, or as stuffing for cushions. There are some traditional medicinal uses for the roots. A glue can be made from the goopy sap in the stems. Here’s my favorite use: dip the “corn dog” in melted wax, and use it for a candle! The wilted male part of the flower serves as a wick.

To plan a visit to the Phinizy Swamp Nature Park:http://www.phinizycenter.org/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed