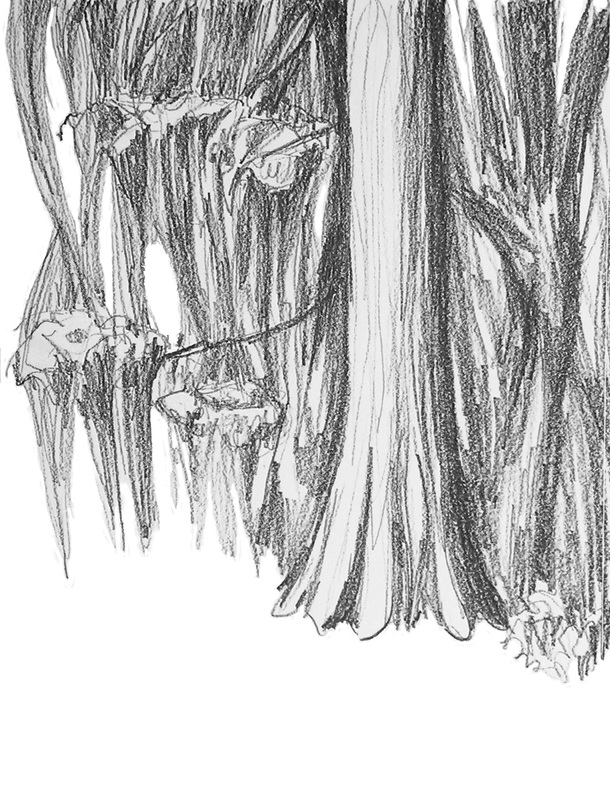

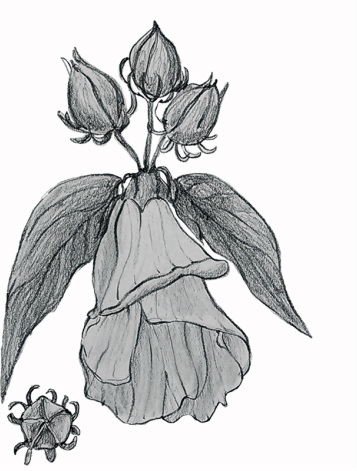

The tickseed sunflower is probably originally native to the Midwest, and gradually spread much further afield. Now it can be found abundantly in wet areas from all the way to the East Coast, and from Ontario to Florida. How did it get here? Presumably it spread by traveling on animals and people.

In a wild format such as the swamp, the seeds of the tickseed sunflower are eaten by an array of birds – ducks and many others.

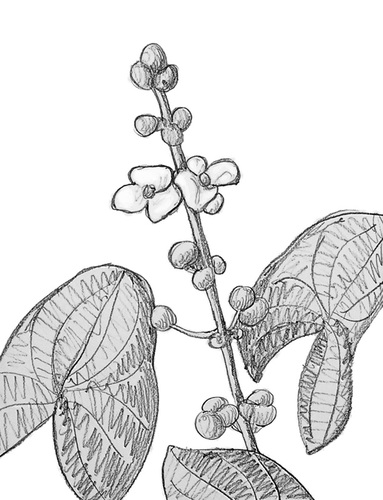

It turns out that biologists are currently revising the Bidens and Coreopsis genera, because now organisms are being analyzed through DNA to determine their degree of relatedness. Before DNA analysis became so readily available, the methods biologists used were direct examination of physical characteristics. So biology categorizations are currently in a state of flux. Both answers I was given verbally can claim to be correct – and tomorrow there may be a different answer.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed